Featured

SEAT POSITION of 16-17th c. – „alla brida”

When looking for a seat that was used in the best educated circles, one should first look for information in the Italian equestrian treatises because in this historical period Italians were considered a role model in this field and you can read about it HERE.

In addition to Italian sources references from other languages

have also been added to show how widely Italian techniques were known in Europe

and to clarify individual issues a little. The article is also supported by

iconography, which will make it possible to compare the image with the

description.

However, the position of the left bridle hand will not be described here,

as this subject requires a completely separate treatment.

„alla brida” & „alla

ginetta”

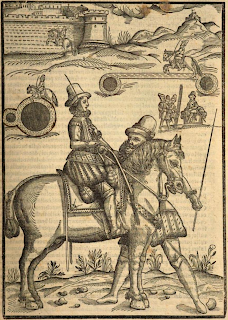

In equestrian books of 16th-17th centuries we can find

descriptions of two main types of seat, that is "alla brida" (Fig. 1)

and "alla ginetta" (Fig. 2). The “alla ginetta” method was mainly used

in Spain and partly in Italy.[1]

The seat

described in this article was called "alla brida" and the

Italian-Spanish dictionary of 1620 distinguishes between the mentioned seats as

follows:

“Cavalgar a la brida. cavalcare con le staffe lunghe, e con le gambe

distese, e non alla Ginnetta, cioè co'pie raggricchiati.”[2]

„Riding „a la brida” [is] riding with long stirrups and stretched legs and it is not [riding] „alla ginetta” which is with the legs tucked up.”

It is worth mentioning that according to Baldassare Castiglione an ideal courtier should be able to sit in any type of saddle and therefore by implication he must be able to take various types of seat.

“Pero'voglio chel nostro Cortegiano sia perfetto Cavalier d'ogni sella (...)”[3]

“I

would hope that our Courtier is a perfect horseman in every kind of saddle

(...)”

ITALIAN SOURCES

Master Antonio Pirro Ferraro created an entire chapter regarding how a rider should present himself in the saddle and entitled it Come star debba il cavaliero a cavallo[4], that is "How a Rider Should Sit on a Horse" (Fig. 4) and his description will represent well other Italian works.

He mentions that the rider should be „il meno affettato” (the least affected), „annervato” (strong), „disciolto” (relaxed) and „star dritto” (sit straight). He is also not to suggested be „colerico” (choleric) and the face is to express „allegrie” (cherfulness).

While Ferraro describes sitting straight, a little further he writes „alquanto il corpo in dietro, & unito con l’arcione di dietro” („the body a little back and united with the hind pommel”).

Ferraro further divides the seat into three parts (two mobile and one immobile).[5]

The first

mobile one is a torso which needs to be relaxed.

The second part is immobile and goes from the waist to the knees. This part is meant to be „quasi inchiodato tra i due borroni della sella” („almost nailed between two saddle pillows”[6]).

The third part is the leg from the knee

down which is supposed to fall towards the girth and the foot should be put two

fingers in the front of the stirrup and forward about half a hand's length and

turned inwards towards the horse's shoulder.

The heel is to be

lowered as far down as possible, which gives more stability. The author also

recommends pointing the heel slightly outwards so that the young and

inexperienced rider could not "cheat" with spurs.

The shoulders should be even. The left hand should keep the reins and the

right hand should hold the rod or a weapon, or it may rest on the middle of the

rider's belt. The elbows are to be slightly moved away from the sides.

The artwork features the below image that perfectly illustrates the seat

described by Ferraro (Fig. 3).

ELEMENTS OF THE

SEAT

Ferraro presented in a precise way the position of a seat, which was also described by other Italian, German, French, English and other authors of equestrian books of the 16th-17th centuries. Below is a list of the elements of the seat followed by informafion regarding who included it in his work.

It is obvious that there were some differences between the individual writers. However, they are so irrevelant that we can still speak of an analogical seat technique.

1. SIT STRAIGHT

To sit straight is mentioned by Palmieri[7], Pluvinel[8], Fiaschi[9], Corte[10], Ferraro[11], Piccardini[12], Massari[13], Galiberto[14], Pieniążek[15] and

Markham[16].

This tip should be read subjectively as it could mean the rider's torso is slightly tilted back as mentioned by Ferraro.

2. AS LIKE STANDING ON THE GROUND

Among others who write about taking positions as if rider was standing on the ground or as if he was on foot are: Palmieri[17], Pluvinel[18], Grisone[19], Fiaschi[20], Galiberto[21], Corte[22], Caracciolo[23], Górnicki[24] or Markham[25].

Again, this should not be taken not literally because when Ferraro (Fig. 3) or Pluvinel (Fig. 4) present the rider’s position, it is clear that the rider is out of balance, which would allow him to stand on the ground. It should therefore be understood as a subjective sense of balance on a horse.

Even Xenophon (circa 355 BCE), who was often quoted by Renaissance authors, wrote to sit „as thought he were standing upright with his legs apart”.[26]

Fig. 4. Illustration a from book of Pluvinel "The Maneige Royal" (1626).

3. HEEL DOWN

About the need to lower the heels down write Galiberto[27], Pluvinel[28], Piccardini[29], Pieniążek[30] and also Ferraro[31] who is explaining:

„(…) il calcagno al

possibile verso basso, laqual cosa, è non solo di molta importanza per tal’effetto, ma ne proviene maggior

fermezza nella gamba (…)”[32]

"(...) the heel as far down as possible, which is not only important for the [correct] effect, but also adds more stability in the leg (...)"

4. LOOK BETWEEN EARS

Looking between the horse's ears is mentioned by Grisone[33], Galiberto[34], Piccardini[35], Markham[36], Pieniążek[37] and Pluvinel[38].

“Hà da tenere la faccia allegra

pigliando la mira nel mezzo dell'orecchie del Cavallo per tenerla dritta.” [39]

„[The rider] should keep a cheerful face by placing his gaze in the middle of the horse's ears to keep it straight [the face].”

Antoine de Pluvinel (France) shows again that this is a subjective matter, as he recommended placing the gaze not only between the horse's ears but also above them.[40]

5. KNEE/ FOOT TO THE HORSE

About the need to turn the foot or the knee to the horse write Corte[41], Galiberto[42], Ferraro[43] and Piccardini[44].

„(…)

voltate le punte di quelli alquanto verso le spalle del cavallo fermandovi in

tal modo di più sulle staffe, che non paia però, che ci abbiate fatto le

radici.”[45]

"(...) turn the tips [of the feet] a little towards the horse's

shoulder blades thus stabilizing yourself more on the stirrups, so that it

doesn't look like you're stuck."

6. CLINGING LEGS

Author requirement that the knees / thighs or legs should be placed tightly

against the horse is recalled by Corte[46], Caracciolo[47], Markham[48], Pluvinel[49], or Pieniażek[50].

„Devete

ben far le radici, per così dire, non ne le staffe, ma ne ginocchi, e nelle

coscie, li quali deveno sempre essere inchiodati non che serrati in sella; dal

ginocchio in giù la vostra gamba sia scioltissima (…)”[51]

"You must take root well, so to speak, not in the stirrups, but in the

knees and thighs which must always be nailed down [but] not locked in the

saddle and from the knee down your leg should be very loose (...)"

7. ELBOWS OUTSIDE

A clue to bend your elbows or your arms out a little is given by Ferraro[52], Piccardini[53], Simoncelli[54] and Pluvinel[55]. Pirro Ferraro laconically states that keeping the elbows tight to the sides will look „bruttissimo” (ugly).[56]

8. CALF FORWARD

An issue worth discussing deeper and which may be ambiguous for us today is slightly setting the rider with calves slightly forward (Fig. 1, 3, 4, 5).

Simoncelli[57], Grisone[58] and Pluvinel[59] mention the fact that

the rider's foot is next to the shoulder blade (or the line of the shoulder

blade).

Galiberto[60], Pluvinel[61], Caracciolo[62] and Ferraro[63] propose to put the legs (calves and feet) forward a little.

„(…) all’hora poi dee annervar le gambe, & ingagliardendosi sù la sella, condurle alquanto più avanti; meno di mezzo palmo in circa (…)”[64]

„(…) there he should then strengthen his legs and firmly in the saddle

leading them a little forward less than about half a hand (…)”

It should be noted that the height

of the horses recommended in equestrian treaties is about 150 cm [LINK], where with such a

short height (according to the current European standards) placing the foot in

the area of the horse's shoulder can be achieved without constraint (Fig. 6).

It would seem that this position of the calf and foot will delay the delivery of the aid, or that the leg aids will be delivered in the wrong place. Pasqual Caracciolo explains that there is a limit to the forward calf setting where the rider loses stability and the ability to deliver aid freely.

„Lo staffile si dee attaccare alla prima fibbia della sella, vicino alle spalle del cavallo, non già alla deretana, perche il Cavaliere cosi porterà più ornatamente la gamba sua lontana dal ventre d'esso cavallo: Non è però da attaccarsi molto appressato allo scontro della sella, perche non sarebbe stare ben forte il Cavaliere, nè il cavallo si potria cosi presto soccorrere con lo sprone, per la soverchia distanza della gamba.”[65]

„The stirrup strap should be attached to the first buckle of the saddle near the horse's shoulder blades, not to the rear, as the rider will carry the leg more ornamentally away from the horse's belly. However, you should not fasten [the stirrup strap] very forward in the saddle because the rider would not sit too strong, nor could he spur the horse so quickly, because the leg is too far [from the horse's belly].”

PLUVINEL GEOMETRY

Although it goes

beyond Italian sources, unique prints from this period where the rider and the

horse are inscribed in a geometric pattern of a tetragon can be found in the

book of Antoine de Pluvinel (1626 - France, Fig. 7) and in works of Ernst

Abraham and von Dehn (1637 - Germany,

Fig. 8) who copied after him.

It is worth to mention that Pluvinel studied horse riding in Italy with the famous Italian master Giovan Battista Pignatelli[66] for six years.

Pluvinel does not explain neither the square nor the vertical lines that he marked in the above illustration and when we translate the text that we find next to the drawing it looks like this:

“RULES

THAT THE RIDER SHOULD FOLLOW

AB The rider's face should

be looking straight between the horse's ears.

CD The shoulders are equally withdrawn creating a little hollow in the back and putting the front part of the waist forward.

EF The left hand holds

the bridle about three fingers above the pommel.

G The right hand is

holding a slightly lowered rod that runs towards the horse's left ear.

H Both elbows

equidistant from the body.

I Legs forward and knees to the horse.

KL The tip of the foot is close to the horse's shoulder and the heel lower than the tip of the foot pivots outwards."[67]

Dehn points out in

his work that he based on Pluvinel and he also does not explain the marked

lines to us and only repeats everything after Pluvinel. [68]

It might seem that in the discussed seat the legs are

deflected in the front of the shoulder-hip-heel line but the tracing of the

line (Fig. 9) shows that the rider still maintains straight posture only is rotated

in the hip axis.

CHANGES IN THE

SEAT

It is worth to mention that in the second half of the 17th century and in the early 18th century the equestrian celebrities began to describe the correct way of riding in a different manner.

In the books of

William Cavendish (1658) [69], Friedrich d 'Eisenberg (1727) [70] or the book of François Guérinière (1731) [71] one can notice a different description of placing

a rider on a horse than the one mentioned by Italian masters. These authors

propose to sit on the crotch and not on the buttocks with the waist pushed

forward where there should be space for a hand between the back pommel and the

buttocks. The legs are to go straight down with the calves not touching the

horse's sides (Fig. 10).

SUMMARY

Although the subject of the seat position will always remain inexhaustible,

the citations of many works by various 16th-17th centuries masters add

something new to the history of equestrianism.

It may be a trap to compare the seat position to the rules and preferences known to us today, because I believe that the method of riding should be considered in terms of the goal that a human wants to achieve while riding. In this case, it would be the training of the rider and the horse to fight which imposes the need for a stable seat with a strong support on the elements of the saddle and such recommendations can be found in the above quotes (and not only).

This seating is probably also a compromise between using a weapon (which has its weight and inertia when wielding it) in combat and performing complicated maneuvers on the battlefield such as circles, snail, snake, reppollone or radoppiare which were recommended to fight. [72]

However, the best proof of the effectiveness of their technique is that in the past the riders were able to perform all of the above maneuvers including the school above the ground such as groppata, capiola, corvetti, salto montone, ciambetta, passeggiare, d’un salto & d’un passo or ballotada.

Taking into consideration gathered

the information it can be assumed that the seat was mainly based on the

"non-mobile" part, i.e. on the pelvis, thighs and knees, as well as

on the belaying on the back pommel and on the saddle pillows called in Italian

„borelli” / „borroni"[73] (Fig. 11) . They were also looking for a solid support on the stirrups.

On the other hand elements such as a torso with a head, hands and calves with feet were to remain mobile.

In books from the 16th to 18th centuries I did not find any mention regarding the "rising" in the trot and although Valerio Piccardini writes:

“Deve il Cavaliero star

avertito à non muovere il corpo, per non pigliar quell onda come fanno li

Postiglioni.”[74]

“A rider must be careful not to move his torso, so as not to wave as the postillions do.”

However, he is certainly not talking about a rising trot, since Piccardini is discussing a canter in discussed fragment of the text.

It is hard to say if the rules of the seat described above were known to

all horse riders. Among the riders familiar with the above technique there are

nobles, to whom equestrian treatises[75] were dedicated, the best educated people[76], riding masters employed at the courts[77] and also members of formations of lanciers such as winged hussars. [78]

PS

I also recommend an article on the same subject by Giovanni Battista

Tomassini:

Below

are additional illustrations of seat from other books by various authors.

REFERENCES:

[3] Castiglione, s.17.

[4] Ferraro, s.40.

[5] Ferraro, s.40.

[7] Palmieri, s.77.

[8] Pluvinel, s.26.

[9] Fiaschi, s.84.

[10] Corte, s.59.

[11] Ferraro, s.40.

[12] Piccardini, s.9.

[13] Massari, s.6.

[14] Galiberto, s.61.

[15] Pieniążek, s.32.

[17] Palmieri, s.77.

[18] Pluvinel, s.26.

[19] Tobey, s.109.

[20] Fiaschi, s.84.

[21] Galiberto, s.61.

[22] Corte, s.59.

[23] Caracciolo, s.366.

[24] Górnicki, s. 42-43.

[25] Markham, s.43.

[26] Xenophon, s.41.

[27] Galiberto, s.61.

[28] Pluvinel, s26.

[29] Piccardini, s.9.

[30] Pieniążek, s.31.

[31] Ferraro, s.42.

[32] Ferraro, s.42.

[33] Tobey, s.107.

[34] Galiberto, s.61.

[35]

Piccardini, s9.

[36]

Markham, s.43.

[37]

Pieniążek, s.32.

[38] Pluvinel, s.26, 29.

[39] Piccardini, s.9.

[40] Pluvinel, s.26.

[41] Corte, s.69.

[42] Galiberto, s.61.

[43] Ferraro, s.42.

[44] Piccardini, s.9.

[45] Corte, s.69.

[46] Corte, s.69.

[47] Caracciolo, s.366.

[48] Markham, s.43.

[49] Pluvinel, s.26.

[50] Pieniążek, s.31-32.

[51] Corte, s.69.

[52] Ferraro, s.42.

[53] Piccardini, s.9.

[54] Simoncelli, s.98.

[55] Pluvinel, s.26.

[56] Ferraro, s.42.

[57] Simoncelli, s.98.

[58] Tobey, s.108-110.

[59] Pluvinel, s.26.

[60] Galiberto, s.61.

[61] Pluvinel, s.90.

[62] Caracciolo, s.366.

[63] Ferraro, s.40-42.

[64] Ferraro, s.40-42.

[65] Caracciolo, s.366.

[66] Pluvinel – „Publisher’s foreword”

[67] Pluvinel, s.29.

[68] Dehn, s.25-26

[69] Cavendish, s.29-30.

[70] Eisenberg, s.36.

[71] Gueriniere, s.40.

[72] Dorohstrajski, s.82,92; Corte, s.96-97; Tobey,

s.251, 253; Caracciolo, s.463.

[73] Ferraro, s.40; Caracciolo, s.363.

[74] Piccardini, s.31.

[75] Dorohstajski – cover; Caracciolo, s.327; Simoncelli, s.4; Corte, s.2;

Gamboa, s.6; Francsco – foreword.

[76] Żołądź, s.7-10.

[77] Rykaczewski, s.200.

[78] Pieniążek, s.31-32.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Pieniążek, Krzysztof. "Hippika albo Sposob Poznania, Chowania Y Stanowienia Koni / Przez Krzysztopha Pieniazka Pisana Anno Domini 1607", Kraków? 1607.

Górnicki, Łukasz. "Dworzanin polski", Kraków; W Drukarniey Andrzeia Piotrkowczyka, 1639.

Wójcicki, Władysław. "Biblioteka Starożytna Pisarzy Polskich", Tom III, Warszawa; s. Olgenbrand 1854.

Dorohostajski, Krzysztof. Hippika to jest księga o koniach. Kraków; Czas, 1861.

Ferraro, Pirro Antonio. Cavallo frenato di Pirro Antonio Ferraro,... diviso in quatro libri. Precede l'opera di Gio. Battista Ferraro,... dove si tratta il modo di conservar le razze,... disciplinar cavalli e il modo di curargli.. Neapol: Antonio Pace, 1602.

Palmieri, Lorenzino. "Perfette regole, et modi di cavalcare", Wenecja; Barezzo Barezzi 1625.

Pluvinel, Antoine. The Maneige Royal. Xenophon Press, 2010.

Fiaschi, Cesare. Trattato dell'imbrigliare, maneggiare, et ferrare Cavalli. Venice: Somascho, 1598.

Corte, Claudio. Il cavallerizzo di Claudio Corte di Pavia, nel qual si tratta della natura de cavalli, del modo di domarli, & frenardi. Et di tutto quello, che à cavalli & à buon cavallerizzo s’apartiene. Venice: Giordano Zilletti, 1562.

Piccardini, Valerio. Scritti de Cavaleria. Około 1600; archive.org

Massari, Alessandro. Compendio dell'heroica arte di caualleria del sig. Wenecja; Francesco Bolzetta, 1600.

Galibero, Battista. "IL CAVALLO DA MANEGGIO". Wiedeń; GIOVAN GIACOMO 1650.

Markham, Gervase. Cavalarice. Or the English horseman”, London: E. Allde for E. White 1617.

Tobey, Elizabeth. Federico Grisone's "The Rules of Riding". Tempe, Arizona: ACMRS, 2014.

Caracciolo, Pasqual. La gloria del cavallo. Venice: Gabriel Giolito. 1557.

Xenophon, The Art of Horsemanship. Dover Publications. 2006.

Simoncelli, Monte. Il Simoncello, o vero Della caccia. Dialogo di Baldouino di Monte Simoncelli. De Signori di Viceno gentil'huomo della Camera del serenissimo Gran Duca di Toscana. Florence: Zanobi Pignoni, 1616

Tomassini, Giovanni Battista. The Italian Tradition of Equestrian Art: A Survey of the Treatises on Horsemanship from the Renaissance and the Centuries Following. Virginia: Xenophon Press, 2014.

Franciosini, Lorenzo. Vocabolario español e italiano. II book. 1620.

Castiglione, Baldassare. IL CORTEGIANO DEL CONTE BALDASSARRE CASTIGLIONE. Venice: Paulo Vgolino, 1599.

Rakowiecki, Wojciech. "Pobvdka Zacnym Synom Korony Polskiey do służby Woienney : Na Expedicyą przeciwko nieprzyiaciołom Koronnym Roku Panskiego", Kraków; Drukarnia Franciszka Cezarego 1620.

Dehn, Ernst Abraham. Kurtze doch eigendliche vnd gründliche Beschreibung von abrichtung vnd Zäumung der Rosse”, Dressden : Bey Gimel Bergen, 1637.

Cavendish, William. "Nouvelle Méthode pour dresser les chevaux... par Monseigneur le duc de Newcastle. Traduction nouvelle sur l'original anglois... par M. de Solleysel,...", Paryż; Gervais Clouzier 1677.

D’Eisengerg. The Art of Riding a Horse or Description of Modern Manege in its perfection by Baron d’Eisenberg. Xenophon PR LLC: 2017.

Guérinière, François. Ecole de Cavalerie Part II Expanded Edition. XENOPHON PR LLC: 2015.

Gamboa, Giovanni. "La Raggione dell'arte del caualcare". Palermo; Gio. Antonio de Franceschi, 1606.

Romano, Francesco. La Perfettione del Cavallo. Rome. Michele Hercole, 1669.

Żołądź, D. (1994). Podróże edukacyjne XVI i XVII wieku - próba typologii. Biuletyn Historii Wychowania, (1), 7-10. https://doi.org/10.14746/bhw.1994.1.2

Rykaczewski, Erazm. "Relacye nuncyuszów apostolskich i innych osób o Polsce od roku 1548 do 1690", Wydanie Biblioteki Polskiez w Paryżu. I, Tomy 1-2, Paryż; Behr 1864.