Featured

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

UNKNOW EQUESTRIAN ITALIAN TREATISE – 1615 (PDF)

While researching Valerio Piccardini’s equestrian treatise, I learned that one version of the manuscript is located in the Kungliga biblioteket in Stockholm with the designation no. E.S. Osign. 79. On March 18, 2024, I had the opportunity to visit the Stockholm library and examine the aforementioned manuscript. However, upon my arrival, it turned out that the book contains not only Piccardini's treatise...

These are: 'IL VERO LIBRO IL

QUALE TRATTA d'insegnare il proprio et giusto modo d'ammaestrare i polledri et

maneggiare Cavalli composto dal famoso cavallerizzo in NAPOLI. 1615’

(anonymous)

and

‘Regole da tenersi per fare Cavalli buoni et obbedienti al cavalcare.’ (that turned out to be a preliminary version by Lorenzino Palmieri before he published it in printed form in 1625).

Fig. 3. Title page of the third manuscript by Lorenzino Palmieri.

All three treatises are written in manuscript form with a uniform style of writing, indicating that they were written by the same person.

TECHNICAL INFORMATION

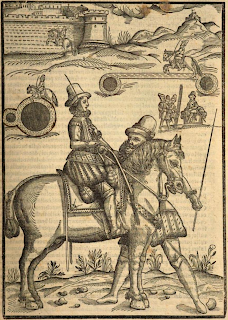

This book is bound in vellum in the format of 13x10cm. Moreover, it contained a few horse illustrations by Joannes Stradanus (16th c.) and a big folded illustration depicting a horse diseases (unknown to me). On the inside cover, there is a glued depiction of the coat of arms of the Engestrem clan that was first ennobled in 1751; thus, we know that at some point this book belonged to this family in the later period.

Fig.

4. One of illustrations by Joannes Stradanus.

Fig. 5. Big folded illustration of a horse diseases added at the end of the book.

Fig.

6. Depiction

of the coat of arms of the Engestrem clan.

The contents of

the book are as follows:

1. Depiction of the coat of

arms of the Engestrem clan.

2. Treatise

by Valerio Piccardini.

3. Treatise

by an anonymous author.

4. Treatise

by Lorenzino Palmieri.

5. Horse illustrations by Joannes Stradanus.

6. Folded illustration of horse diseases.

UNKNOWN TREATISE

My particular attention was drawn to the second treatise

by an anonymous author titled 'IL VERO LIBRO IL QUALE

TRATTA d'insegnare il proprio et giusto modo d'ammaestrare i polledri et

maneggiare Cavalli composto dal famoso cavallerizzo in NAPOLI. 1615’ which

literally means: 'The

real book which deals with teaching the proper and correct way to train young

horses and manage [experienced] horses composed by the famous horseman in

Naples. 1615'.

After a deeper

analysis, comparing it with other known Italian treatises, and checking the

terminology used by the author, I am almost certain that it is an unknown

Italian equestrian treatise.

Fig. 7. Title

page of the unknown anonymous equestrian treatise.

CONTENTS

The treatise does not contain any introduction, as the

author begins by describing the principles of horsemanship on the first page.

It also lacks a conclusion, except for the words 'Il fine.' (The end). In the

content, the author includes recommendations for riding young horses, to

addressing problems that arise in working with them, when to start learning

'roppolone' (passade), using 'posata' (raising the front of the horse),

performing 'raddoppiare' (pirouettes), a maneuver called 'corvette' (similar to

the modern terre a terre), air above the ground maneuvers such as ‘salto’

(jump), 'capriole', 'passo e salto', correct positioning of the horse's head,

rules for using spurs and the crop. The last part of the treatise deals with

describing the structure of a 'good' and 'bad' horse mouth, bad habits that

arise from using the bit, and recommendations regarding the bit itself.

One of the more interesting information I found is the following description of ‘raddoppiare’ a type of tight pirouette:

"...dipoi voltate sopra il trotto due volte tanto largo quanto fusse una girata di carro Napolitano..." ("...then perform two circles in the trot as wide as the turn of a Neapolitan carriage..."). However, I couldn't specify exactly how wide the Neapolitan carriage turned.

Describing the correct execution of 'raddoppiare', the author emphasizes the importance of the horse placing its legs one over the other stating:

“...e quando il

cavallo caminera a questa rota la gamba vostra di fuora vada sempre a passare

sopra quel la di dentro...” ("...and when the horse is executing this circle, its outer leg

should always pass over the inner one..."), because if the horse fails to do so and if the horse gets

"stuck" with its hindquarters, "...saria pericoloso e

brutto..." ("...it would be dangerous

and ugly...").

Additionally,

the author points out that the size of the circle of such a pirouette must „…non piu larga d’un corpo di cavallo...”

("...not exceed the size of the horse's body..."). From "Il

Cavallerizzo" by Claudio Corte (1562), we know that this refers to the

radius of the circle, and the length of the "horse's body" is

measured from its front hooves to the rear.

The author also

describes the bending during this kind of pirouette:"...al raddoppiare fate piegare un poco la testa e che sia tanto

poco che non venghi a piegar il collo che solamente basta a mirare dove

volta." ("...in 'raddoppiare,'

slightly bend the head [of the horse], so delicately as not to bend the neck,

it suffices that [the horse] just looks where it is turning.").

We can also find confirmation that the "posata" (lifting the front of the horse while engaging the hindquarters, similar to the modern levade) was used in the past to teach "salti" (jumps in the air), which are elements of airs above the ground school.

The author, unlike many others, very clearly divides the action of spurs into three phases: adjusting, aiding and punishing. “Lo sprone si deve aggiustare in tre modi, o per aggiustare o per aiutare o per gastigare, per aiutare ha d'essere pian piano, per aggiustare ha d'essere piu forte, e per gastigare ha da esser fortissimo.” („The spur must be adjusted in three ways, either to adjust, to aid, or to punish. To aid, it must be gentle; to adjust, it must be stronger, and to punish, it must be the strongest.”).

We can also find recommendations regarding the length of the "guardie" (curb bit’s shanks), as the author proposes shanks with a length of "una palmo" (a measure unit called "palmo," approximately 26 cm) for a horse type described as "coursier" - "...fate delle due [guardie] per corsieri d'una palmo..." („… prepare two [sets of shanks] for coursiers of one palm…”).

From other

Italian authors of that period, we learn that curb bit’s shanks should not

exceed the length of exactly one "palmo." Therefore, for this type of

horse, the author of the discussed text theoretically proposed the longest

shanks possible .

To sum up, this is one of the few treatises that does not describe the entire process of training a horse from the very beginning. It does not even describe how a specific maneuver/element should be technically executed as a whole. The work of this anonymous author is actually very brief and is aimed at riders who already have a good understanding of maneuvers. It focuses on avoiding mistakes, solving problems with a horse, and emphasizing what is most important for the correct execution of each element. Unlike other equestrian treatises of that era it does not cover topics such as: horse colors, breeding, shoeing, equine medicine, etc., as is often found in other Italian equestrian treatises of that era.

It is a concise

essence of the art of horse riding, devoid of things obvious to an experienced

rider.

ASSUMPTIONS

In the 16th to 18th centuries, it was fashionable for

nobility to undertake foreign travels for educational purposes (including

learning horse riding). It happened, as in the case of Valerio Piccardini's

treatise, that students copied their master’s treatise and took it home to help

them remember what they had learned.

I suspect that

probably an unknown Swedish nobleman visited Italy in 1614/1615 for the purpose

of learning various arts. Valerio Piccardini was employed at the Academia Delia

in Padua during this period, which is located in northern Italy, hence Piccardini's

treatise was probably transcribed first and dated 1614.

Then, the same

nobleman traveled south and transcribed a second treatise by an unknown author

in Naples in 1615. There is no date for the writing of the third treatise

authored by Lorenzino Palmieri. Subsequently, the nobleman mentioned above

probably returned to Sweden with the manuscript, where at some point it

eventually ended up in the hands of the Engestrem clan, and then in the Royal

Library in Stockholm.

PREVIEW IN PDF

Below I am providing an anonymous treatise found in PDF format for public preview.