Featured

SPURS /SPRONI

Spurs at 16-17th century were called "sproni"[1]

in Italian, "spurs"[2]

in English, "éperons"[3]

in French, and "sporen"[4]

in German.

This entry is only a portion of the knowledge of how to

deal with spurs recommended in 16th-17th century equestrian treatises. However,

it is worth quoting a few interesting fragments to understand the approach of

people of that time and to show which type of spurs was preferred.

This article is based on selected fragments from books

written by 16th and 17th century equestrian masters, as it is the most trustworthy

sources of knowledge.

It is worth to begin with a quote from the famous

mid-16th century equestrian master Federico Grisone:

„Però quando tenerete lo staffile di sopra

il genocchio, verrà à cavalcarsi più lungo, et affettato mirando ciascuna punta

de vostri piedi al dritto della punta dell'orecchia del cavallo, & non al

dritto della spalla, come alcuni dicono, perche sarebbe falfo; Questa foggia di

cavalcare, con lo staffile di sopra il genocchio, antichamente era più da

galante, & in uso, per causa che i cavalieri, à quel tempo usavano molto i

cavalli armati di barde, & bisognava (per arrivare al ventre di quelli) che

i sproni fossero lunghi circa un palmo (…)”[5]

„However, when you hold

the stirrup leather above the knee [in front of the knee], you will be riding

with a longer [stirrups straps], and unnaturally pointing each tip of your feet

in a straight line with the horse's ear, and not straight to the shoulder, as

some say, because that would be a mistake; This way of riding with a stirrup

straps above the knee [in front of the knee] was more elegant and used in

antiquity [middle ages?] because riders at that time used horses heavy armed

with „barde” [horse armor] and it was necessary (to get to their belly [horse's

sides]) than spurs were to be about a hand long [26.37 cm] (...)"

This passage tells us that by the time Grisone wrote his treatise (1550), long-legged riding was abandoned, and it was the seat that determined the length of the spur.

Graphic of „Die

Heiligen Drei Könige mit Gefolge”- 1450-1455. Seat and

type of spurs abandoned by Fiaschi and Grisone.[6]

Pasqual Caraciolo in 1566 criticized previous generations

for introducing spurs too late in the training of a young horse:

„Ma nell'uso di essi sproni peccavano

già gli antichi, iquali nõ gli davano mai, fin che il Cavallo non fusse stato

intendente di tutti gli ordini, onde avvenia, ch'egli lungamente assicurato con

l'aiuto della bacchetta, e de i calcagni piani, al novo sentire delle spronate

divenia vitioso; e quanto più era attempato in possanza, e robustezza, più

restava incorretto, perche come sbigottito per le novelle punture, e confuso

della volontà del Cavaliere, spesso andava à traverso, over à salti, ò trahea

calci;”[7]

„But in using spurs the

ancients sinned, because they never used it until the horse was mastered in all

the rules / exercises, hence for a long time they used the rod and heels

[without spurs], a new touch of spurs adds vigour; and when it was used more

powerful and forceful, he [the horse] was more incorrect, as if shocked by the

new stings [of the spurs], and confused by the rider's will, he often walked to

the side, even jumped or kicked;”

An interesting fragment describing which type of spurs

were used in the initial stage of riding a horse can be found in the work of Lorenzino

Palmieri from 1625:

„Il cavallo deve farsi con lo sprone, e castigarsi quando fallisce, et avvertire, che quando si maneggia, si appicchi con esso tanto, che lo riceva per aiuto, et che per quello aiuto risponda allegramente senza dispetto, e senza accorarsi, e questa è la maggiore difficoltà, che consista nella Cavalleria. E questi sproni devono esser a bottone, perche tali sproni non aviliscono, ne accorano il cavallo, ma faranno che egli si correggerà d'ogni errore, e se li darà più facilmente l'intelligentia delli sproni, et per assai, che il Cavaliero si accendesse di collera, e battesse impetuosamente, non si accorerà, come farebbe per li sproni con le ruote pungenti. Et il sprone a bottone tiene il cavallo ubbidiente, che havendo preso l'intelligenza delli sproni saprà fare ogni cosa. Lodo, che poi si cavalchi con ogni sprone per assai, che punga, perche all'hora non bisognerà altro, che cennarlo, che effendo lui intelligente del sprone vi risponderà ad ogni minimo cenno. Adunque alli principi per far nascere questi buoni effetti servitevi delli detti sproni a bottone, et con quelli farete il vostro cavallo sofferente, corretto, giusto et animoso.”[8]

„The horse must be made [trained] with a spur, and punished when he makes mistakes, and I inform you that when [the horse] is managing, apply it [spur] a lot that he receives it as a help, and he responds to this help cheerfully and without grief, and it is the greatest difficulty of equestrianism. And these spurs must be rounded[9], because such spurs do not damage or injure the horse, but will force him to correct every mistake and will make it easier to remember [the help] of the spurs for a long time, and if the rider will be overwhelmed with anger and hit violently [with spurs], he will be not as sorry as if he would do it with spurs with sharp wheels. And the rounded spur keeps the horse manageable, he will remember about the spurs, he will know how to do everything. I praise you for riding with spurs for a long time, that you add them because you will have to do nothing but remind [the horse] the memory of the spurs, it will make him react to every little sign. Therefore, for the rules that are to produce these good results, use the aforementioned rounded spurs, and with their help you will make your horse more tolerant [?], correct, proper and spirited.”

People of that time were also aware of the nuances of

this tool:

„Non continuate a battere il cavallo

con uno sprone solo; perche con ciò se gl'insegna a mirare i fianchi.”[10]

„Don't hit your horse

with just one spur; because this way you teach him [the horse] to look at [his]

hips.”

Battista Galiberto (1650) wrote not

to overuse this equestrian aid:

(…) Non si deve in alcun modo dare molte speronate al cavallo, perche le molte speronate l'aviliscano, e li fanno perder la forza, & volontà, e diventà restivo, mal creato, e fà li calli duri alli fianchi, che poi non li curà più, e non ne fà stima; è però li castighi devon' essere temperati con misura per conoscer' il cavallo, & il cavagliero sia chiamato virtuoso, savio, e valoroso in tal virtù; (…)”[11]

„You must not in any way give the horse many times spurs,

because the many uses of spurs will weaken him, and make him lose strength,

& will, and it will become reluctant, badly created, and makes the calluses

hard on the sides, which then will not cure them and he will not respect them [spurs];

however, punishments must be limited with measure to recognize the horse, and

the rider will be called to be virtuous, wise, and brave in this virtue;”

For balance, a fragment should be added where in the case

of lazy horses it was recommended to treat them severely.

„Ma'un

cavallo che fusse duro, & pigrissimo, ai sproni, & difficile alle volte

radoppiate, quando fa incavallar le braccia, voi sdegnosamente in luogo

stretto, ò veramente nella campagna, voltandolo con quella furia, che se ne può

cavare, senza pausa niuna lo batterete continuamente di sproni, cosi come si

suol aiutare, & tanto spesso, che da i lati appresso le cegne se gli faccia

sangue.”[12]

„But when a horse is reluctant and unresponsive to the

spurs, and difficult to do radoppiate [modern pirouette] when he crosses his

legs, you should turn him contemptuously in a tight place or in a field with

fury as much as you can, and you will keep hitting the spurs like a normal aid,

and so often that from the sides below the girth until blood appears. "

Federico Grisone adds at the end of his work that such

actions are extreme and should be avoided and punishments should be used fairly

and deliberately. [13]

Such an

opinion was presented in his book by Alois Podhajsky in 1967.

„The spur should be used only in

advanced stage of training, and only when required to reinforce the pushing

aids. The use of the spurs is last resort and, as with other things in life,

the last resort should be reserved for emergencies. The spur should touch the

horse’s side with an increased pressure of the leg and the application should

be discontinued the moment the aid has obtained the required result. The spur

should never be used sharply as an aid, becouse it would then no longer be an

aid but a punishment.”[14]

Alois Podhajsky also points out

that the spurs should be fastened at the right height, to be used without

overly changing the position of the body.

„The spurs, which reinforce the leg aids, should be fastened to the boots in such a way that the rider should be able to touch the horse behind the gitrhs without rising his heel. At the Spanish Riding School the traditional spur is turned upwards as the Lipizzaners are relatively small and spur turned down might induce the rider to rise his heel in order to touch the horse.”[15]

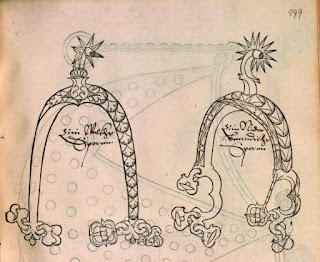

Below is presented a collection of the types of spurs selected only from equestrian treatises and recommended by the masters of 16-17th century.

[1] Tobey, s.109.

[2] Markham, s.75.

[3] Noue, s.142.

[4] Künstlicher, s.43.

[5] Tobey, s.108-110.

[6] Tobaey, s.108-110; Fiaschi, s.105.

[7] Caraccioo, s.385.

[8] Palmieri, s.7.

[9] In oryginal „bottone” what mean buton. At that time, the button was ball shaped.

[10] Palmieri, s.35.

[11] Galiberto s.57.

[13]

Tobey, s.357, s.XXI.

[14]

Podhajsky, s.58.

[15] Podhajsky, s.247.

BIBLIOGRAFIA:

Tobey, Elizabeth. Federico Grisone's "The Rules of Riding". Tempe, Arizona: ACMRS, 2014.

Markham, Gervase. Cavalarice. Or the English horseman: contayning all the art of horsemanship, asmuch as is necessary for any man to vnderstand, whether hee be horse-breeder, horse-ryder, horse-hunter, horse-runner, horse-ambler, horse-farrier, horse-keeper, coachman, smith, or sadler. Together, with the discouery of the subtil trade or mystery of hors-coursers, and an explanation of the excellency of a horses vnderstanding. London: E. Allde for E. White 1617.

Noue, Pierre. La cavalerie françoise et italienne, ou, L'art de bien dresser les chevaux, selon les preceptes des bonnes écoles des deux nations: tant pour le plaisir de la carriere, et des carozels que pour le service de la guerre. Lyon, Morillon, 1620.

Johann, Fayser. Künstlicher Bericht und allerzierlichste Beschreybung des edlen, uhesten, unnd hochberümbten Ehrn Friderici Grisonis neapolitanischen hochlöblochlin Adels. Warburg, Getruckt zu Augspurg, 1573.

Caracciolo, Pasqual. La gloria del cavallo. Venice: Gabriel Giolito, 1587.

Dorohostajski, Krzysztof. Hippika to jest księga o koniach. Kraków; Czas, 1861.

Palmieri, Lorenzino. Perfette regole, et modi di caualcare di Lorenzino Palmieri fiorentino. Wenecja; Barezzo Barezzi, 1625.

Wójcicki, Władysław. "Biblioteka Starożytna Pisarzy Polskich", Tom III, Warszawa; s. Olgenbrand 1854.

Fiaschi, Cesare. „Trattato

dell'imbrigliare, maneggiare, et ferrare cavalli”. Wenecja, Somascho, 1598.