Featured

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

SADDLE FROM WIELUŃ CIRCA 1400

A

Saddle from Wieluń dated to the Turn

of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries

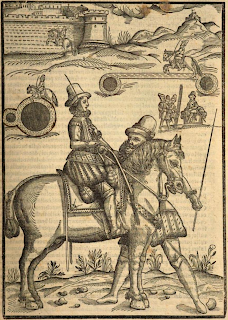

Saddles of a similar shape can be found in late medieval iconography, from the fourteenth to the fifteenth century, as can be seen from illuminations and sculpture (Figures 1 and 2).

Fig. 2.

West Portal of the Basilica of Brothers Minor

in Strzegom - 1375.

Photograph

by Marcin Ruda

1. Place of Discovery

During the archaeological excavations conducted in 2010/2011 under the supervision of the archaeologist Bogusław Abramek with the support of Waldemar Golec, the head of the museum's archaeological department, the remains of a saddle were found in the collapsed basement. The research was carried out within Królewska - Barycz streets in the city of Wieluń. The place of finding on a map from the sixteenth century is marked below (Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Map of Wieluń in the sixteenth century

Archaeologists described this place as a former basement, i.e. a place located below the ground floor, partially located below the ground level. The room was most likely employed as a repair shop or repository for used everyday items.

The basement collapsed and buried the shop in the

second half of the fifteenth century. This resulted in cut off and insulation

of the layer. The contents of the basement are dated to 1370-1450, and this

dating is adopted for the saddle found in the basement.

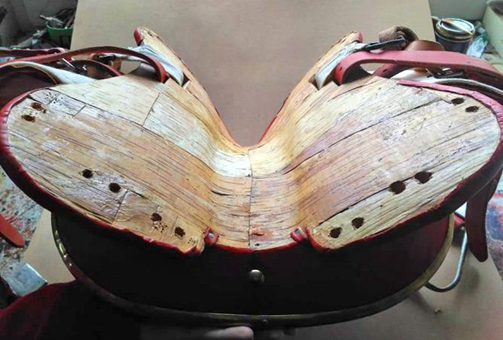

2. Quality of the Artifact

Under one of the collapsed beams, the remains of a saddle were found in good condition. The artifact was already damaged, i.e. the tree was broken in several places and there was no right bar, no rear pommel metal fitting, no stirrup leathers and stirrups, no girth and no pillows (see Figures 4 and 5).

The wooden structure has been preserved in an

almost perfect condition, retaining its profiles, dowels, traces of processing,

brad spots, birch bark coating, holes, etc. The leather cover is also in very

good condition. The leather is still strong and flexible with visible sewing

holes, brad spots, traces from production and numerous marks of use.

Fig. 4.

The saddle during the cleaning process. Photograph by Waldemar Golec.

Fig. 5. Discovered wooden, leather and metal components of the saddle.

Drawing

by Marcin Ruda

3. The Saddle Tree

As mentioned above, the construction of this saddle is unique among the examples that have survived to date. The wooden structure is made of an unidentified type of wood with distinct straight grains. The structure consisted of 5 large wooden elements, 6 dowels with a diameter of about 12 mm and birch bark (Figure 6).

Fig. 6.

A – front pommel, B- left bar, C- cantle, D- seat connecting element.

Photograph

by Waldemar Golec

It is clear that the construction of the tree was well thought out. It is complicated in its shape, because the lack of precision in one element affects at least three elements at the same time, which makes it difficult to match them together. The wooden elements are deliberately arrange for the grains to follow a certain pattern, which again indicates experience in technology (Figure 7).

Fig. 7.

The arrangement of wood grains in the tree elements. Drawing by Marcin Ruda.

The pommel was connected to the bars with two

dowels (one on the left and one on the right), and the cantle with four. The

seat connecting element (D) shows no signs of joints. Most likely it was glued

on, and it is probable that all the elements of the tree were glued together.

The only preserved bar has two rectangular openings: front (about 60x15 mm) and

rear (about 30x10 mm). The front slot is wider and was most likely used for

attaching the girth, while the back, narrower slot most likely was a hole for a

stirrup leather. In all elements, except for the seat connecting element, you

can see the preserved remains of the tips of the brads without the heads.

The description shows that the brads were

silver-grey with large (about 13 mm), strongly semi-circular “heads.” On the

front pommel, there is also a strongly corroded fragment of the edge fitting of

greyish color.

In the left bar, the only one preserved, there are

three pairs of holes in its front part. The upper pair of holes is 8mm in

diameter, the middle one is 10mm, and the lower one (partially visible) is also

8mm. Pairs of holes with a diameter of 8 mm, similarly to other artifacts, were

used to attach the saddle pad. A pair of holes with a diameter of 10 mm is

probably a breastplate mounting system typical for that period.

On the underside of the bench, there are loose

elements of birch bark coating. The glue that held them has disintegrated over

the years. The bark would have been glued to protect the saddle from horse

sweat or other moisture from penetrating into the wooden structure due to the

high content of betulin in the bark.

No traces of arrangements that would preserve the

saddle against air moisture have been found. The tree, apart from the leather

outer covering, was not otherwise protected, although such protection would

remain between the felt layer and the wood.

4. The

Leather Elements

The origin of the leather has not yet been determined. It is approximately 1.5-2 mm thick and has a compact structure. Many elements have survived, ranging from entire saddle panels to small torn scraps. Despite the passage of several hundred years, the skin is still strong, elastic and compact.

The colour most likely blackened due to years of

lying in the ground.

Fig. 8.

Half of a seat cover. A- cantle, B- pommel, C-flap. Photograph by Marcin Ruda

Fig. 9.

Two halves together. Cantle view. A- print of the cantle fitting,

B-Brads

spots, C- sewing holes. Photograph by Marcin Ruda

Fig.

10. Other leather items. A- outer cover of the cantle, B- outer cover of the

pommel,

C-cover

of the front part of the left bar, D and E- most likely the straps masking the

base of the cantle. Photo graph by Marcin Ruda

There are many signs of usage on the leather, such

as: bruises caused by lifting the flap of the saddle (e.g. fastening the

girth), tension in the area of brads mounting, scratches,

cuts during production, sewing holes (diamond-shaped holes), bruises from

pommel fittings, corrosion under the front pommel fitting.

Between the leather of the seat and the tree, many

traces of a thick (about 1-2 cm) layer of felt were found. It was located on

the entire surface of the seat and under the flaps (see Figures 8, 9 and 10).

Thanks to the preserved marks of use, it can be

concluded that the saddle had been used for a prolonged period of time.

5.

Reconstruction

Unfortunately, the number of elements and their condition after conservation did not allow for the use of photogrammetry. However, the method of creating a foam model based on tracing the preserved elements and then transferring it to a 3D model turned out to be effective (see Figure 11).

Fig.

11. A foam model of the saddle tree. Photograph by Marcin Ruda

To create the model, 1:1 scale drawings of the preserved elements were used as well as and the cross-sections of wooden elements (Figures 12 and 13).

Fig.

12. The profile of the cantle and, at the same time, the cross-section at the

level of the seat. Photograph by

Waldemar Golec.

Fig.

13. The final effect of creating a 3D tree model. Photograph by Marcin Ruda

The next step was to process the 3D model into

paths compatible with a CNC milling machine and milling individual elements in

the wood, as illustrated on Figure 14. Figures 15-16 show the fitting of

leather elements and the finished saddle.

Fig.

14. Wooden elements of the tree reconstruction. A-

front pommel, B- bars, C- cantle, D- seat connecting element. Photograph

by Marcin Ruda

Fig.

15. Adjusting the outer cover of the seat. Photograph by Marcin Ruda.

Fig.

16a and b. Finished saddle reconstruction. Photographs by Marcin Ruda

6. The Pillows

On one of the saddle bars, we can find two pairs of smaller holes (8mm). They are located in front of the left bar at the top and bottom edges and are of a similar size and position as in other saddles of the same period (Figure 17).

Fig.

17. Two saddles from 1459-1519. Visible pillows under the saddle, tied by

holes.

Photograph

by Marcin Ruda

Another important element indicating that the saddle clearly had a tied pillows is the structure of the bottom of the tree (see Figure 18). There is no clear and sufficiently deep channel to isolate the horse from pressure on the spine.

Fig. 18. The birch bark covered underside of the saddle without pillow.

Photograph by Marcin Ruda

The original also lacks a

curvature of the front parts of the bars outwards or a rounding, because it was

the underlay that created the necessary rounding at the edge of the horse’s

shoulder and the rest of the surface in contact with the back (Figure 19).

7. The

Girth System

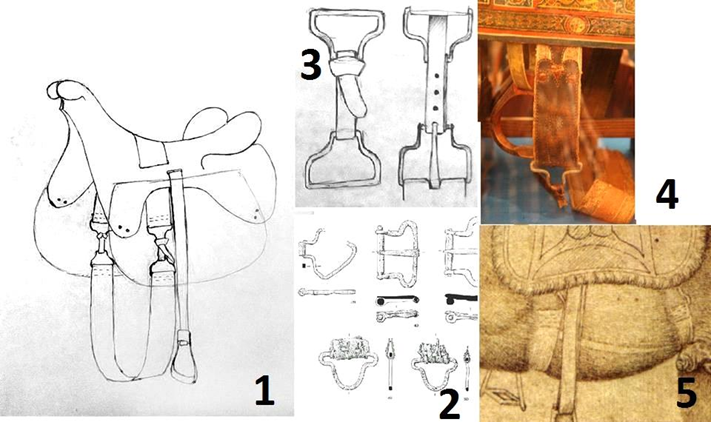

There are two oblong rectangular holes arranged diagonally in the preserved saddle bar, the larger one above the smaller one. This arrangement is found in many ornamented saddles from the fifteenth century (see Figure 20).

Fig.

20. A decorated saddle from 1439 with visible analogous holes. Photograph by

Marcin Ruda

However, there is no artifact that would unequivocally dispel doubts about such a girth system.

Below (Figure 21) I present the concept of the

fastening system. Elements of such a solution are not unfamiliar to us, because

to date they are used in such countries as Hungary, Pakistan and Egypt as well

as in “western” saddles.

Figure

21. 1. The concept of the fastening system. Drawing by Marcin Ruda

2.

T-shaped buckles known as “harnechement de monture” (John Clark, The Medieval Horse and Its Equipment, c.1150-c.1450).

3.

Alleged use of T-buckles. Drawing by Marcin Ruda

4.

T-shaped buckle on the eastern saddle from the sixteenth century. Photograph by

Marcin Ruda

5.

T-shaped buckles from the drawing of Pisani Pisanello from the middle of the

fifteenth century.

John Clark in his work The Medieval Horse and Its Equipment, c.1150-c.1450

describes

the use of T-buckles as part of the girth system.[1]

Such a girth system gives a precise tightening of the girth and the possibility

of a stronger fastening (no holes determining the strength of fastening). The

importance of the length of the girth is also decreasing, because it all

depends on the length of the billet straps, and in the event of its breakage or

wear, it is easier to replace in relation to the straps attached to the tree.

8. Test

Riding

Three different horses were used for the tests. Two with a height corresponding to the fourteenth and fifteenth century standards, i.e., between 131 and 152 cm[2] and one outside this range (Figures 22-24). The rider’s height in the test is 170 cm. On the other hand, the average European height in the Middle Ages was 173.4 cm.[3] The critical factors here are the size of the horse and the shape of its back, as well as the size of the hips and the length of the rider's legs.

The seat chosen

for the tests also comes from the iconography of the corresponding period,

characterized by the rider's legs straight or slightly bent and slightly or

strongly extended forward with the torso straight or somewhat tilted back

(Figure 25).

Fig.

22. The first horse is 158 cm tall. Photograph by Marcin Ruda

Fig.

23. The second horse - 146 cm tall. Photograph by Marcin Ruda

Fig. 24. The third horse - 134 cm tall. Photograph by Marcin Ruda

Fig. 25. Walk, trot and canter. Photographs by Patrycja Gil

On the first horse (158 cm), the saddle tended to roll slightly on its back, mainly when the rider was mounting. The saddle also covered a relatively small area of the back. In case of the second (146 cm) and the third (134 cm) horses, the saddle did not tilt when mounting and also covered a relatively greater part of the back. The saddle at the rider’s seat has a “raised” cross profile, which imposes a foreward leaning posture.

Due to the fact that the saddle does not have a high cantle, the rider has the ability to freely

lean back and create a shock absorber from the hips and lumbar section that

works up and down in line with the animal's movement

in trot and canter.

Fig.

26. Reconstruction showing the girthing system. Photograph by Marcin Ruda.

References

[1] John Clark, The Medieval Horse and

Its Equipment, c.1150-c.1450 (London, 1995).

[2] Clark, Medieval Horse.

[3] Richard Steckel, Health and Nutrition in the Preindustrial Era: Insights from

a Millennium of Average Heights in Northern Europe (2001).