Featured

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

NOSEBAND - WHY?

MUSSAROLA /NOSEBAND/NAGĘBEK

Today, there are many types of equine element that we know by the term "noseband".

Few, however, can explain without hesitation where it came from and why it was introduced.

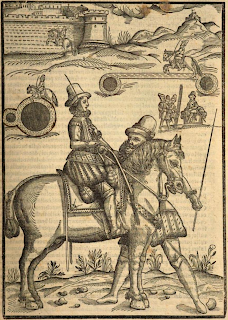

In more than the half of iconography of the Middle Ages, this element in the horse bridle is not noticeable. The frequency seems to have increased since the mid-16th century.

Often in the equipment of eastern origin, we can notice decorated elements (naprysk) in bridle commonly known today as noseband, which can be systematically divided into 3 different technical solutions:

1. Combination of two separate elements: a "nagłówek" with a "uździenniczka" (cannot act as a "noseband"):

Below connection of "uździenniczka" with "nagłówek":

2. Decorated "nagębek" (noseband) permanently attached to the "nagłówek" (headband), but without the chinstrap (cannot function as a "noseband"):

3. Noseband permanently attached to the "nagłówek" with a chin strap (can act as a noseband):

„The

musarola is very praiseworthy, because if the horse naturally carries his mouth

closed, it will not harm him, and even if he has his mouth open, not only will it do him good, but it corrects him of this problem, so that being inured with

this, then (whatever you remove it [musarola]), he will be totally corrected so that he

will go forth always with the right mouth and great restraint. It will make him

set of head, neck, and arch, so that, walking forward, he always rests correctly

on the bit. And I do not answered to those who want to criticize [musarola], because it is evident that their criticism stems from the limited experience

that they have of it.”

Lorenzino Palmieri in his work "Perfette regole modi di cavalcare" from 1625, I wrote:

„La musarola aggiusta la bocca, e fa pigliare appoggio; ma non da liberta di lingua portando il cavallo briglia chiusa.”[2]

“Musarola

corrects the mouth and gives you support; but it does not give the tongue

freedom by keeping a horse closed with its bridle. "

“Really Mussarola deserves a

lot of praise, because if a horse has a naturally closed mouth, it cannot harm

him; and even if it opens it a lot, it helps and corrects in such a way that

being used to it (although it is already removed), it will always walk with

real support and a good "mouth", keeping the mouth closed and the

tongue correctly with a stable head , and bent neck.

Which support [mussarola]

above all else is appropriate and necessary for the horse, not even when he is

doing fermo à fermo or repolelons, but when he is walking, when he is trotting

or galloping or running; it will always be the same signal, steady and

strong in losses & strokes

However, be warned,

Mussarola must not be so close [tight?] that the horse cannot breathe; unless

he is too willing to open his mouth too much or press against the hand: "

Robichon de la Gueriniere in the "Ecole de Cavalerie" from 1736 in a translation from 1979 wrote about "muserole" [4]:

„First of

all you see if the throat latch is not too tight, otherwise it would restrict

the horse's breathing. For the noseband it is the opposite, it should be kept a little tight

to prevent the habit some horses have of keeping their mouths open. It also

puts a stop to those whose fault is bitting one’s boot. After this, make sure

that the bit is not so high as to wrinkle the horse’s lips at the corners of

his mouth nor should it be so low that it is carried against the teeth [canine].”

It is also worth inserting a citation from the last century for comparison. Below Alois Podhajsky, one of the former directors of the Spanish Riding School in Vienna. Quotations from The Complete Training of Horse and Rider - 1967:

„…the noseband, fastened under the bit, prevents the horse from opening his mouth and crossing his jaws, a bad habit often found with young horse. It also prevents the horse from yealding with the lower jaw instead of at the poll in order to evade the discomfort of bending.”[5]

also

„The noseband must be on the nosebone and not on the cartilage. The chin strap must be fastened under the bit and be loose enough to allow the horse to accept titbits from the hand; it should be tighter with the horse that opens his mouth or crosses his jaws and looser for one with a quiet mouth.”[6]

Graphic: "The Complete Training of Horse and Rider” – 1967 – Alois Podhajsky

Considering only the opinion of equestrian masters and apart from the pathological use of this element, the reason for using it has been the same for hundreds of years.

There is no one rule how tightly it should be tightened, it should be adjusted individually to the horse.

REFERENCES:

[1] Tobey, Elizabeth. Federico Grisone's "The Rules of Riding". Tempe, Arizona: ACMRS, 2014, s. 287

[2] Palmieri, Lorenzino. "Perfette regole, et modi di cavalcare", Venice; Barezzo Barezzi 1625, s. 7.

[3] Caracciolo, Pasquale. "La gloria del cauallo. Opera dell'illustre s. Pasqual Caracciolo, diuisa in dieci libri: ne' quali, oltra gli ordini appartenenti alla caualleria, si descriuono tutti i particolari, che sono necessari nell'alleuare, custodire, maneggiare, & curar caualli; ..", appresso i Gioliti, Venice; 1585, s. 362.

[4] Guérinière, François. "École de cavalerie: contenant la connoissance, l'instruction et la conservation du cheval", Paris; chez Jacques Guérin, 1736, s. 153.

[5] Podhajsky, Alois. "The complete training of horse and rider", London; HARRAP 1967, s. 240.

[6] Podhajsky, s. 241.